Q: Tell me about the novel you’re working on. When did you originally start the story? How did it evolve? What was the original kernel or acorn that became the story?

It’s the story of a baseball pitcher’s struggle with autism from childhood to the major leagues. I started the story around 2007 as a collection of my own autistic thoughts and tendencies fleshed out in awful scene snippets which would make even a bad experimental novel cry. The story was really born when I started the low-residency MFA at Southern New Hampshire University and my mentor, Wiley Cash, showed interest in the idea and pushed me to try other narrative approaches. I suppose the kernel was own experience growing up in an era when autism spectrum disorders were a relative unknown combined with my family’s history in baseball, particularly pitching.

Q: Give me a brief bio of your life:

I grew up and still live just south of Los Angeles and remember writing little stories of my daydreams since about second or third grade. As a child I loved sports, especially hockey and baseball and going to games with my Dad and Uncle David. I did a lot of camping and hiking with the Boy Scouts on my way to Eagle Scout. When I got older I took interest in philosophy which took my writing in a different direction for a while before I found my way back home to fiction again.

Q: What would you say are your strengths as a writer?

Most importantly, I take criticism well. I also read everything as a writer and editor, trying to dissect it and see what makes the heart beat and see how that applies to my own work, my own projects; to that end, I take a lot of notes while reading any book. I’m never satisfied and always try to learn and keep honing my craft.

Q: What are you working on now?

The novel for the most part, but I’m also working on some short stories, in particular a satire of the recent rash of American gun violence. My big project for the year, though it’s likely to take more than one, is a non-fiction effort about my favorite musician, Chuck Schuldiner, who was the front man for and creative force behind the band Death.

Q: What publications has your work appeared in?

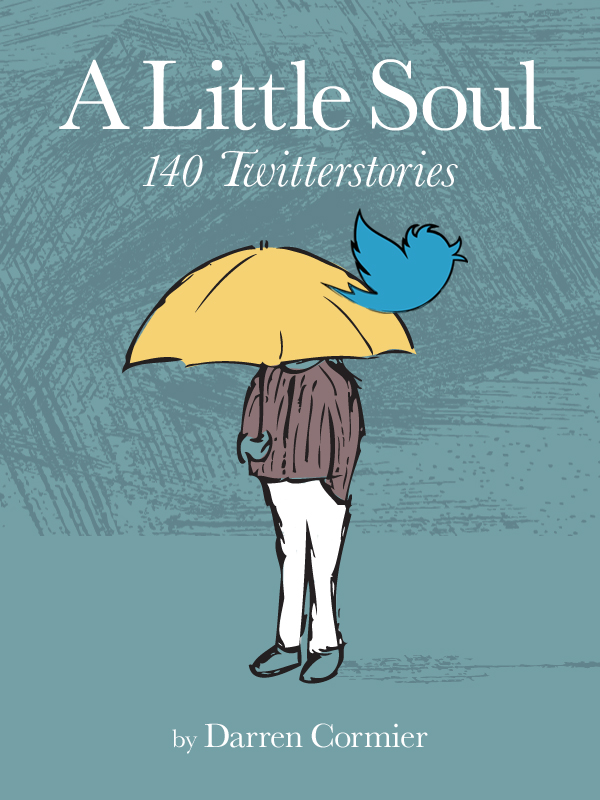

OneFortyFiction

Q: Who are your primary influences, or inspirations, as a writer?

One of my best friends from high school has pushed me to write since I’ve known her, but I first got the idea of writing in my head at my local branch library. My parents left me there to read while they attended to something, and I found Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles and saw how a man put his daydreams, his fantasies, to paper. I was sold; I started dreaming of typewriters and, some years later, laptops. I’d have to sit around my parents’ offices a lot after school as well, so I’d find an unused typewriter and plot out my daydreams—at least, when I wasn’t making colossal paperclip chains. My mom has an English degree and got me to loving books real young. Seeing her write, even to little or no acclaim, gave me the affirmation I needed. Kids are so often short on confidence and long on doubts, it was nice having that as a beacon growing up.

Q: How has your upbringing influenced your work, if at all?

Being autistic obviously affects my WIP, the baseball novel, but having a physical disability probably had more influence. It hardened me, made me stronger, and gave me a more adult perspective to weigh my writing against. In elementary school, instead of stories about GI Joe and ninja fantasies, I’d write detective stories about serial killers and horror stories about things that go bump in the night.

Q: What inspires you the most (e.g. music, landscape/nature, written word, life, etc.)?

I’d have to say life, because I don’t really know otherwise. Sometimes you can’t sleep and are in bed watching Demolition Man for the five thousandth time, when epiphany strikes and the what-ifs start rolling around; sometimes a conversation sparks an idea for a story; sometimes the loathing of some existing aspect of human culture does it, especially when I get to writing satire.

Q: What are you reading right now?

Bang the Drum Slowly by Mark Harris and What We Saw at Night by my current and rocking mentor, Jackie Mitchard. The latter is really cool because the main characters have a genetic flaw that they don’t see as this big setback. I can really empathize with the way they think, that no holding back mentality. I’ve never had characters be so close to home for me.

Q: What authors, when you read them, make you think, “I’m giving up writing because I will never be as good as them?”

Raymond Carver comes pretty close. My writing mantra is “WWRCD?” Less is more, lean is mean, and all that jazz. Sometimes, though, a little poetry-spiced prose really lets that daydream form, and Toni Morrison weaves that into narrative with beauty and tension in the same breath. I try to strike a balance between the two.

Q: I know this is the hated and borderline unanswerable question, but it has to be asked. Why do you write?

I daydreamed a lot as a kid. Writing them down as stories was a way to share the process of make-believe outside of the playground. More than anything else, writing is a way to give the daydreams a reason to be, like an action figure is a reason to be talking to yourself, belly-down on the carpet.

Q: If you weren’t writing, what else would you be doing?

Playing and teaching guitar probably. I used to be on track for a career in law, but I wouldn’t trade writing for that ever.

Q: Name your top five favorite books and/or top five favorite authors?

In no particular order: Brave New World, Aldous Huxley; To Kill a Mockingbird, Harper Lee; What We Talk About when We Talk About Love, Raymond Carver; anything by Ray Bradbury; Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert M. Pirsig.

Q: What is your non-writing claim to fame?

I got my picture in the paper as a kid for being a wicked awesome Push-Cart Derby driver who could make the Kessel run on a wooden palette in under twelve Parsecs.

And now we get into the non-writerly, more silly-ish questions of the interview, as paraphrased from James Lipton of Inside the Actor’s Studio:

Q: What is your favorite drink?

Rum and Coke with a lime twist.

Q: What is your favorite curse word?

Asshat, though my favorite cursing of all-time is the chained diatribes of the dad in Christmas Story. That guy could out-swear two sailors and a pirate with mere gibberish.

Q: Favorite food.

Pepperoni, black olive, and roma tomato pizza with Newcastle or Longboard beer, and I’m a big fan of Señor Fish’s fish tacos.

Q: What is your most vivid memory?

I’m not sure I have a most vivid memory, but I can remember almost everything since age three. My second earliest memory is dancing around in my parents’ living room to Michael Jackson’s Bad playing on a little Fisher-Price tape recorder.

Q: What is your favorite sound?

Ocean waves lapping on the beach, that steady rhythm of the Earth’s pulse.

Q: What is your least favorite sound?

Dog alarms, like people mount on their fences. Any real high frequencies like most people don’t hear really. Forget ADT, I can be stopped dead in my tracks by a dog alarm.

Q: If heaven exists, what do you think god will say upon meeting you at the pearly gates? What would you want it to say?

Probably, “I told you so, jackass.”

I’d want a god to tell me the journey isn’t over yet, that I was interesting enough to merit a sequel. Truth be told, I’d like to make the Singularity and live forever. Wouldn’t it be cool to see the Sun eat the Earth from the safe distance of some colony on one of those Kepler planets? What happens when the universe ends or does it?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed